Hugo Ehrlich, the architect from Zagreb, was educated in Vienna at the end of 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. The new age that arrived with such great violence had not yet been deprived of its illusions at the time of his creative peak. People still believed that the advance of technology and rational thinking could make the world a better place. Nearing thirty, in 1908 Ehrlich took over the task of finishing the Villa Karma on Lake Geneva, started by Adolf Loos. He remained in touch with him, and with Viktor Kovačić he was to work for some time in a shared studio.

Ehrlich went from traditionalism to modernism relatively quickly and smoothly. His buildings are still important landmarks on the architectural maps of the cities he worked in.

Hugo Ehrlich died at the age of 57. People say that he was a very introverted and defensive person who rarely showed what he felt, and hardly ever made public statements about his views and opinions. At the age of 50 he began the construction of the Yugoslav United Bank in Belgrade.

While in the second half of the last century there was a great deal of research into and evaluation of the local modernisms in Zagreb and Ljubljana, followed by a presentation of its most brilliant authors to the world, some of them having achieved international recognition, in Belgrade the issue of modernism in architecture was first tackled in a factual manner just over a decade ago by Zoran Manević and other authors, mostly art historians. They wrote about the life and works of the architects, but there was no basic synthetic study on the architecture of that time until the publication of Modernism in Serbia – The Elusive Margins of Belgrade Architecture (MIT press, 2003) by Ljiljana Blagojević.

Because of this, the architects from the age of modernism who designed some of the most important buildings in Belgrade are still relatively unknown. They were not only from Serbia – in the period between the two great world wars, Belgrade was also built by those who happened to be there, some of whom later went on to have successful architectural careers elsewhere. There were those who came to Belgrade upon invitation by the clients. They would construct several buildings and move on, only later to be shown that their Belgrade buildings were very essential in their architectural body of works.

Hugo Ehrlich, a distinguished architect from Zagreb, is one of those who were invited to build in Belgrade. All of his four buildings still exist: the Boys’ School and the Evangelist Church in Zemun, the Nikić residential building on the corner of Dositejeva street and Simina street, as well as his most important one, the Yugoslav United Bank. Their function remained mostly unchanged (except in the case of the Evangelist Church), but unfortunately, due to unprofessional remodelings, some of their architectural values have been lost forever. This goes above all for the Yugoslav United Bank building, designed in 1929 and constructed in 1931.

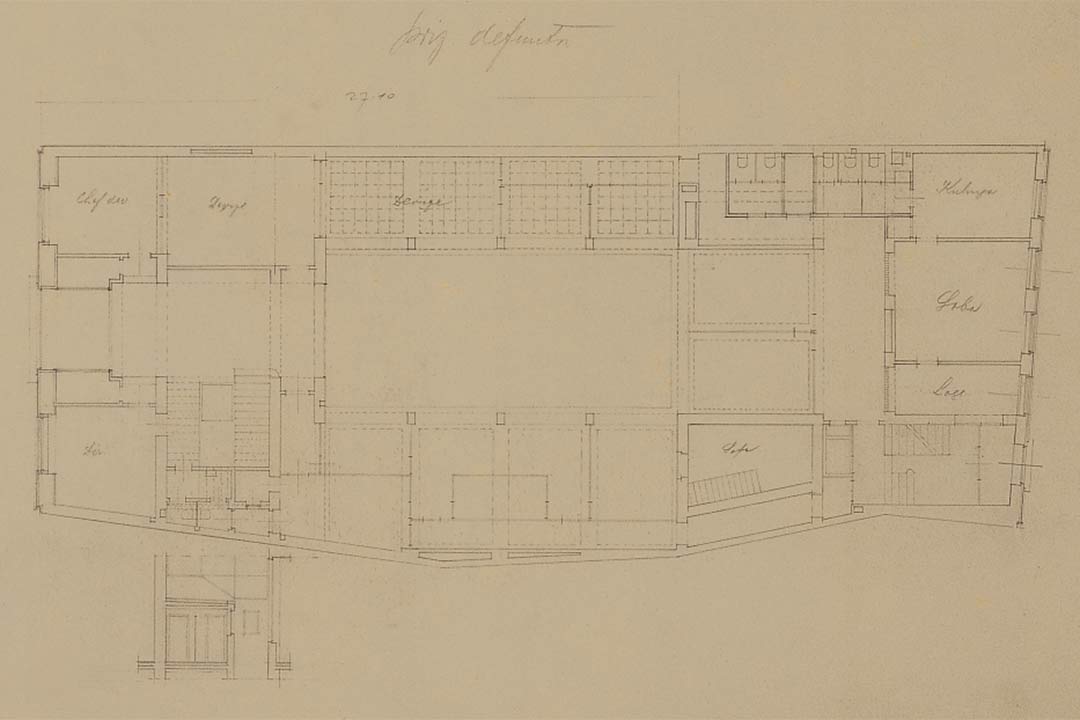

For two years Hugo Ehrlich fought with the Belgrade Building Office, which was not very keen on modernism. They asked for changes to be made to the original design created for a narrow plot of land between Kralja Petra Street and Rajićeva Street. In Kralja Petra Street there was already the Serbian National Bank, designed in the academic style in 1890 by Konstantin Jovanović. In the 1830s, in that part of the town along the Kalemegdan, the first administrative and political center of Belgrade and Serbia, later of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, was formed. Important in the financial, political, administrative and religious sense (the Orthodox Cathedral is nearby), that part of the town was marked by its academic and national style. This is probably the reason why there was so much resistance to a modernist project. In his first design, Ehrlich gave the façade in Kralja Petra Street a modernistic look, with straight lines and a rhythm of openings in line with the function of internal spaces. The number and size of the windows was determined by the arrangement and function of the rooms, and they were not the same for each floor. However, the rhythm of window openings in the final design was more uniform. Ornamental arches above the openings on the third floor were a concession to the predominant traditionalism of the milieu and the actual notion of representative quality.

The Yugoslav Investment Bank is Hugo Ehrlich’s only exclusively office building. Žarko Domljan, who wrote a study of this architect, sees this as a reason for “the cold formality of the facade”. Compared to the previously ornamental façades designed by Ehrlich, this one in Belgrade – subdued and rational – perhaps looks cold, yet it completely fits into the basic postulates of modernism: the façade appearance is derived from the building’s function and is devoid of any excessive ornaments. This building was completed not long after what Domljan calls the watershed year of 1928, when Ehrlich “almost suddenly abandoned traditional forms and accepted the contemporary principles of architectural volume design”. This could also be the reason for this “cold formality”. The façade of this Belgrade bank looks as if it were modeled after something very similar – although not treated in such a functionalistic way – the facade of the First Croatian Trade Bank in Ilica Street in Zagreb, completed in 1924. It dates from the time when Ehrlich was still developing his modernistic attitude. This connection is stressed by the same simple sign lettering that in both cases functions as an essential architectural element.

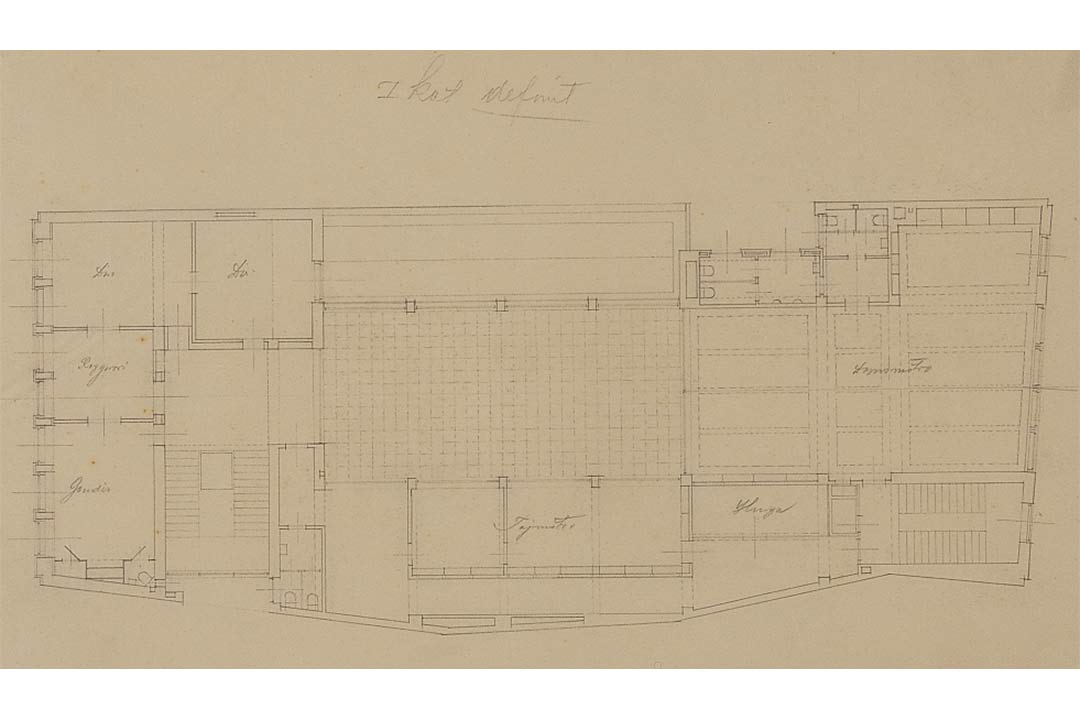

The Belgrade Building Office did not worry so much about the other facade of the Yugoslav United Bank, the one from Rajićeva Street, so the architect was able to carry out his functionalistic ideas literally. The arrangement of the openings reflects the interior – the staircase vertical, the horizontal strip of office windows, and the detached window on each floor for the department heads.

Ehrlich demonstrated a very advanced approach in the design of the interior of the cashier’s hall of the Yugoslav United Bank: in accurate and rational design, simple lines of the furniture and the lamps, the new, precious materials, Marcel Breuer’s chairs designed in Bauhaus, and everything studied to minute details. Light coming from above makes the space airy, attractive and light. Both Žarko Domljan and Ljiljana Blagojević agree that the interior of the cashiers’ hall is one of the highest achievements of modern architecture in this region between the two world wars.

The building was published in many professional journals of the time. The representative quality of the space, simplicity, measured tone, spirit of the new age... All that can be seen on a photograph taken in thirties of the last century, not long after the building in Kralja Petra Street was completed. Seventy years later, the facade is still the same, but there are only hints of the previous interior. Almost nothing remained of the bank’s functional and modernist office space. Ignorance destroyed what time could not. Redesigns during the sixties disfigured the cashiers’ hall to the point of unrecognizability, and there were many conversions in the offices upstairs. Some of the Ehrlich’s concepts could be divined in spaces on the first and second floor. Still left are the massive wooden tables and big prestigious chandeliers with missing pieces. The corridors still have some of the “regular” differently shaped round glass lighting fixtures. The furniture and the interior elements that remained from Ehrlich’s time on the upper floors of the bank point to the presumption that only the cashiers’ hall was consistently built in the spirit of modernism, and that in the interiors of the other spaces the architect kept some of the elements for equipping the rooms and halls of that purpose characteristic for that time. The staircase volume with a metal railing and handrails was not touched, but with the installation of lifts and many conversions, it was devastated as well.

Today, the Yugoslav United Bank building in Belgrade is surrounded by other banks. Some of them, monumental and powerful, were built very recently. Hugo Ehrlich’s bank is waiting for someone with the financial strength, sensitivity and knowledge to restore it to its old glory.