The historical materialist approaches a historical object only where it confronts him as a monad. In this structure he recognizes the sign of a Messianic cessation of happening, or, put differently, a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed history. He takes cognizance of it in order to blast a specific era out of the homogeneous course of history – blasting a specific life out of the era or a specific work out of the lifework.

Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History[1]

Sanja Iveković has questioned and provoked the dichotomy of the public and private since her first works from the early 1970s (these are concepts that, since Ancient Greece, have related the private to necessity and – it does not need to be emphasized – to space occupied by women, children, and slaves, and the public as a sphere that starts exactly where any necessity ceases and in which citizens discuss matters apart from and beyond mere life, things bereft of personal or private interests) and has constructed all of her works on the ruins of this myth. Whether we talk about video, collages, media interventions or so-called public works, they are all characterized by co-relating and equating the so-called personal therefore private, and the so-called public therefore political, and this, as splendidly analysed by Bojana Pejić[2], by means of a ‘personal cuts’ strategy, a procedure that rests on techniques of collage and editing.

In the opposition public/private, such as we encounter in discourse about art in public space, public space is still equated with consensus, coherence and universality, thus relegating pluralism, division and differentiation to the realm of the private. As Rosalyn Deutsche established, compromise and harmony, homogenization and harmonization are not the essence of public space, public space is determined by exclusions; she suggests defining it by means of ‘its production’, therefore not as something constant, but as something that emerges in the moment of a conflict, as the space of dispute. Public spaces, says Deutche, ‘are structured by exclusions and moreover, by attempts to erase the traces of these exclusions. Exclusions are justified, naturalized, and hidden by representing social space as a substantial unity that must be protected from conflict, heterogeneity and particularity.’[3] In other words, public space is constituted by what it excludes. In her works, Sanja Iveković operates with the term ‘public’ exactly in order to problematize the very division public/private. As we will see in the analyses that follow, her works do not proceed from public space as a finite fact, but as a concept that can multiply political spaces, being oriented exactly to the traces of exclusions Deutsche talks about. Here, I will limit myself to two of her works: one intervention in the domain of public sculpture and one intervention in the media space that connects dealing with historical time as historiography and the question of the representation of a woman in this time.

Lady Rosa of Luxembourg was realized in the spring of 2001 as part of the exhibition ‘Luxembourg et les Luxembourgeois’, organized by the Luxembourg City History Museum and Casino Luxembourg – Forum for Contemporary Art.

For this occasion,[4] Sanja Iveković decided to create a replica of a local monument, Le Monument de Memoire, known in Luxembourg as ‘the Golden Woman’ (‘Gelle Fra’). The monument was erected in 1923 as a memorial to Luxembourg soldiers who fell in the First World War. On the top of an obelisk, there is a gilded figure of Nike, the allegory of victory, and she holds a laurel wreath to crown the soldiers who fell in the war. In 1940, the monument was hidden by Luxembourg workers of fear of the German occupiers and it remained far from the public until it was re-erected in 1985.

Sanja Iveković cuts (to retain the appropriate term, inaugurated by Bojana Pejić) this national icon with three (feminist) interventions: she dedicates her temporary monument to a historical figure, the revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg; the figure of Nike is transformed into a pregnant woman; and the base of the monument is wrapped in text. The intervention provoked an enormous political scandal in Luxembourg, angry reactions of the public to an ‘endangered’ national identity, reactions in the media, on the very location of the monument (interventions by passers-by, like placards reading ‘Rosa Go Home’), and even in the Luxembourg Parliament. I will refer briefly to each of the three interventions separately.

Monuments dedicated to freedom emerged throughout Europe after the First World War and Gelle Fra is not a special case in this respect, more of a rule. Equally, it is not surprising that victory is represented by a female figure and that this representation of a woman in public space is generic and symbolical in opposition to male figures in public space that are usually individuals, great historical personalities. With her intervention, Sanja Iveković turns this historical injustice around – she gives the name of revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg to the allegory of victory, the goddess Nike, ‘the Golden Lady’. The allegory is transformed into a real historical person.

Furthermore, Lady Rosa of Luxembourg is pregnant. Since this is a national icon, we can open space here for conversation about the nation as a productivist story. Let us also add the fact that the monument is placed in the city and country of Luxembourg, a banking centre and tax oasis, a place of reproduction of capital. Here, as noticed by Rastko Močnik,[5] it is convenient to recall Friedrich Engels and his work The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State. The significant contribution of Engel’s criticism rests on the fact that historical materialism, as the science of the production of things and survival, has brought about another dimension, namely: reproduction of species and reproduction of humans. The relationship between capitalism, as reproduction of things, and its social condition, as reproduction of humans, is complementary. There is no structure without its conditioning. Therefore, we can interpret the pregnancy of Lady Rosa of Luxembourg as that structural pattern of production of things, therefore of the nation as well, and so also national territory, and that is reproduction of people.

German art historian Kathrina Hoffman-Curtius, talking about this work, said once that it repeats the patriarchal matrix instead of criticizing it. In opposition to that, Bojana Pejić opened an interesting question: the issue of women who were raped in wars, who were not ‘fallen heroines’, but ‘fallen women’, which evokes an entirely different set of associations, one that dwells in the ethical registry. The key for such an interpretation lies in the third intervention, in the text that clothes the base, which communicates in three languages and in three different registries. The text in French is La résistance, la justice, la liberté, l’indépendence; in German Kitsch, Kultur, Kapital, Kunst; and in English is Whore, Bitch, Madonna, Virgin. The combination of these words and registries broadens the interpretative field and opens up questions of the connectedness of national liberation, capitalism, culture, art, war, religion. It reminds us that space is not innocent; that it is not a neutral platform where equally valid interventions are confronted and, eventually, the best one wins (the myth, by the way, about the market, entirely rooted in liberal discourse, within which the public sphere is perceived as neutral). Palpable evidence of this is the decision by Parliament which was passed on that occasion. A law was brought in that restricted even artistic expression, in a country of a hundred-year-long democratic tradition. Namely, the Parliament of Luxembourg passed a new law after this event that protected Gelle Fra as a national symbol and thus from any misuse, even artistic![6]

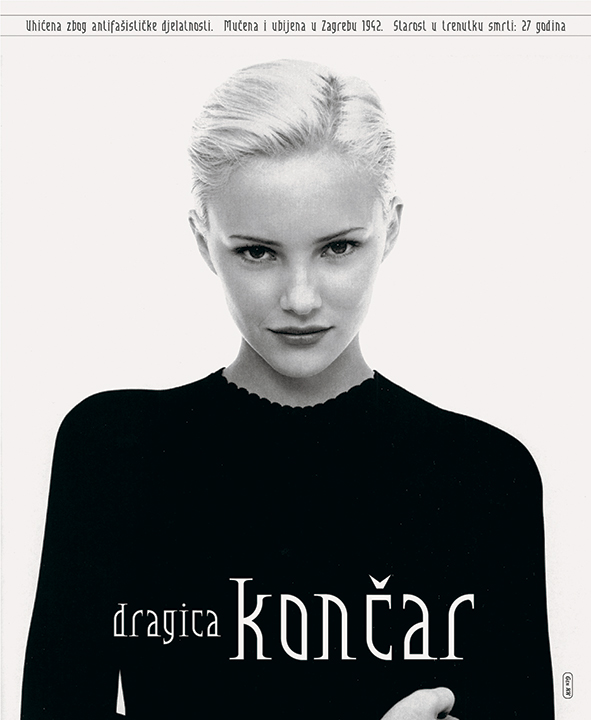

Let us now turn to the second example, Sanja’s media project Gen XX (1997-2001), a work that dates from the time after state socialism was defeated, in which she intervenes, again with the technique of collage – this time photography, fashion photography of course (photographs of models, therefore advertisements) and texts (short biographies of some national heroines of the antifascist fight who were executed during the Second World War) – in the media space. During 1997 and 1998, the photographs were published in the format of advertisements (and they were not any different except for the added text) in magazines Arkzin, Zaposlena, Frakcija, Kruh i Ruže, Kontura.[7]

Sanja Iveković often uses female magazines as material and at the same time, as the area of the fight in which gender and national identities emerge. This turning-point that appeared in the format of Sanja’s works after the mid-1990s, a time when she started to step forward to the public space more and more (the conventionally understood one, in other words, democratic public space as a permanent sphere in which, according to Habermas’s model, citizens participate in rational discussion on equal grounds, as a sphere of general inclusiveness and accessibility), seems to me crucial for her artistic procedure. The importance of this turning-point is not the fact that her work ‘shifted’ to the public sphere at that time, but the fact that since that time her works started to deal with Yugoslav antifascist history which was, in the construction of the new national identity, repressed as a trauma, banned from public discourse, public space, school books… all part of the national euphoria in which history started all over again.[8] Sanja Iveković has persistently exhibited precisely this banned history, repressed political fights: Gen XX is truly a site-specific public manifestation (Croatia, late 1990s), but it is also a time-specific attempt to reveal the processes that happened in all other post-communist ‘democracies’ which aspired, without exception, to erase any possible connection with the past.’[9]

The analyses could be continued and extended to the entire opus of Sanja Iveković dedicated to themes of gender, identity and memory in which they are deconstructed and re-edited by means of the artistic procedure of ‘personal cuts’, all in order to show/reveal their social conditioning. In these two selected works these three major themes are interwoven and reported as supports of the same myth about the allegedly neutral public sphere. ‘Cuts’ by Sanja Iveković tore open the surface and revealed traces of exclusions that blur the harmonious image of public space. With this analysis of these works, I wanted to show how Sanja Iveković problematizes the public/private dichotomy by showing how instances of exclusion are naturalized and hidden by representing social space as true unity, as well as how the artist translates aesthetic tools into those of the political struggle. In the end, perhaps she can best say it in her own words, in her statement on the occasion of her Mohnfeld Poppy Field intervention,[10] performed at the Documenta 12 exhibition in Kassel in Germany: ‘As the red colour is at the moment slowly taking over Friedrichsplatz, hope grows in me that it will be transformed into a “red square”. And perhaps, sometime in the future, Friedrichsplatz will become Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz.’[11]

[1] Walter Benjamin: Critique of Violence, edited and with an introduction by Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, New York, 1968, p. 263.

[2] I refer to the study by Bojana Pejić ‘Public Cuts’ in Sanja Iveković: Public Cuts, ed. Urška Jurman, The P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Institute, Ljubljana, 2006.

[3] Rosalyn Deutsche: Evictions – Art and Spatial Politics, MIT Press, Cambridge, 1998, p. 281.

[4] The history of this work is somewhat longer and I do not have time to present it in this context. Therefore I would like to refer to the study ‘Lady Rosa of Luxembourg, or Is the Age of Female Allegory Really a Bygone Era?’ by Bojana Pejić in In the Place of the Public Sphere, ed. Simon Sheikh, b_books, Berlin, 2005.

[5] I refer to an unpublished lecture by Slovenian sociologist Rastko Močnik, which was held in Net.culture Club MaMa in Zagreb in 2005, organized by the artistic group Community Art. The theme was the relationship between contemporary art and politics.

[6] The controversy caused by the work of Sanja Iveković was not the first controversy in relation to this monument. Namely, when the monument was unveiled in 1923, her tight dress provoked disapproval because it was not decent.

[7] It certainly has to be emphasized that these are not mainstream magazines, but alternative, intended for small audiences or again, specialized in art.

[8] Rastko Močnik talks about this new kind of orientalism: ‘The notion of the ‘East’ performs a historical amnesia. It erases the political dimension from the eastern past, and achieves similar effects in the present.’ Quoted in: Boris Buden: ‘The Post-Yugoslavian Condition of Institutional Critique: An Introduction’, Transversal web magazine: http://eipcp.net/transversal/0208/buden/en

[9] Bojana Pejić: Sanja Iveković: Public Cuts; ed. Urška Jurman, the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Institute, Ljubljana, 2006.

[10] This was an intervention in front of Fredericianum, the central building of the exhibition. The artist planted a poppy field on a green surface (on which a feudal master used to train his troops and Joseph Beuys, also as part of Documenta, installed his 7000 Oaks in 1982). The field consisted of two kind of plants – red, field poppy and opium, purple poppy. An integral part of the exhibition was also an audio recording of nine revolutionary songs, performed by choirs of Zagreb’s activist/lesbian group Le Zbor and female group RAWA from Afghanistan. These were reproduced two times a day via large speakers in the public space of the square. In this manner, Friedrichsplatz became a red square during Documenta, but also a favourite location for visitors to the exhibition and passers-by to take photographs.

[11] http://archiv.documenta12.de/index.php?id=1049&L=1